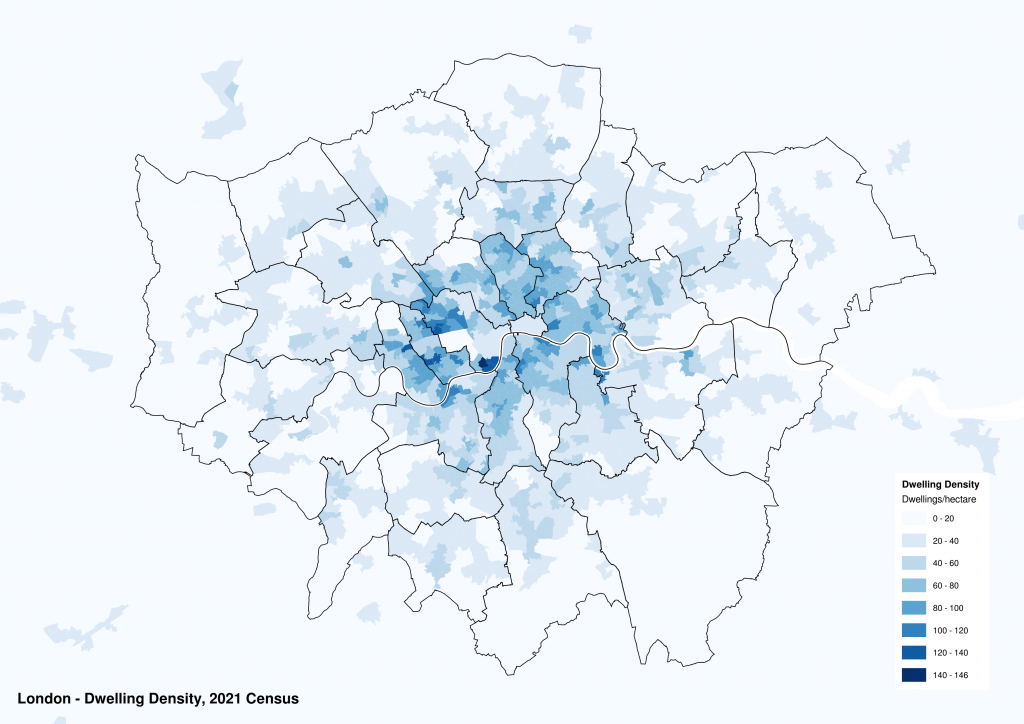

In comparison to other similarly-sized world cities, London is not very dense. With limited exceptions, such as Maida Vale, parts of Tower Hamlets and Kensington, much of the city has no more people per hectare than the satellite towns surrounding it. Arrive by train and this is only too apparent, with railways cutting through miles of two-storey Victorian terraces, only giving way to mansion blocks, high rise towers and high-density housing estates close to the heart of the city. Our housing is too thinly spread.

All land in London is a precious resource, and to sustain our capital’s economy and vitality we have to use it more effectively—and more fairly.

Living in any major city—and benefiting from all of the amenities and conveniences that it has to offer—comes with a moral responsibility to allow others to do the same. London’s suburbs in particular could do much more to help provide the homes that the city so desperately needs—no more so than in those areas which benefit from good access to the public transport network, and where reliance on private car ownership diminishes.

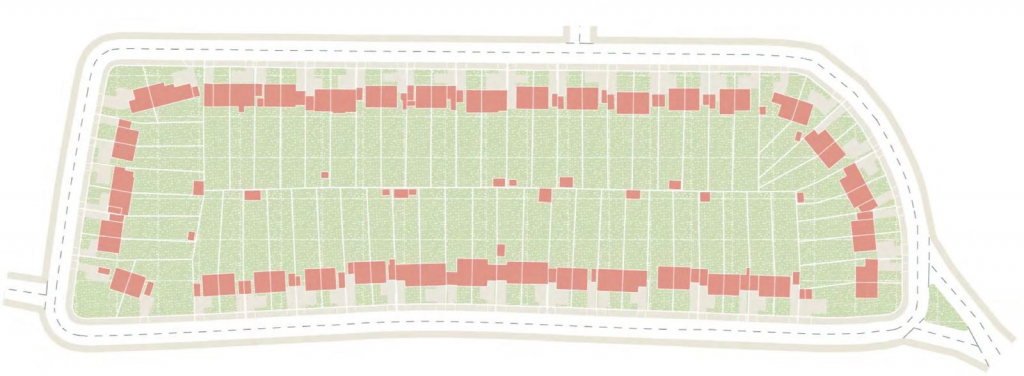

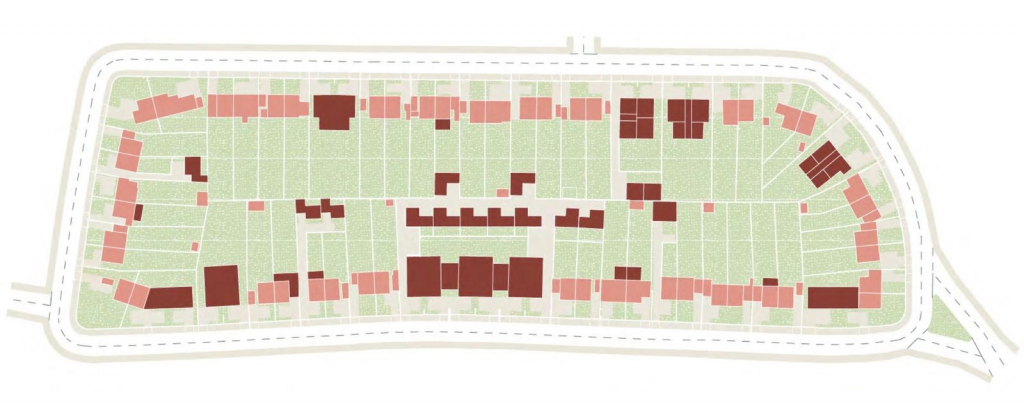

But in outer areas which have not been identified for large-scale regeneration, the process of intensification can be a tortuous one. Obtaining permission to build even a small development of new homes is disproportionately complex, time-consuming and risky when compared to larger strategic developments.

Yet, even within existing planning policies, all the tools exist to establish an environment where land seemingly lost to low-density housing can actually be reinvigorated through a process of gradual densification.

Focusing on areas within a ten minutes’ walk of the city’s suburban train and Underground stations, there is the potential for up to a million new homes to be built, surprisingly quickly and effectively.

When Mayor of London Sadiq Khan’s London Plan was adopted in 2021, it set out, for the first time, housing targets that must be achieved on small sites in each of the London boroughs, the City of London Corporation and two Mayoral Development Corporations. In this case, small sites were defined as anything with an area of less that 0.25 hectares—roughly a third of a standard football pitch. Accompanying these targets was guidance and policies on how such development should be encouraged through plan-making and decisions.

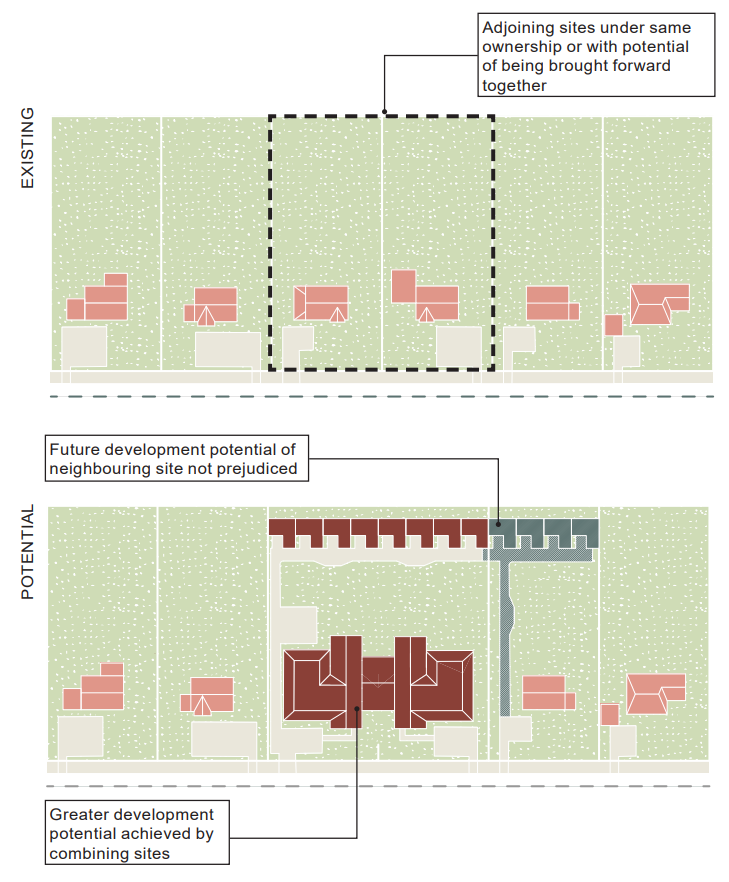

Although it didn’t become formal policy until 2021, Khan’s version of the Plan had first been published in draft form at the tail end of 2017. The boroughs either embraced or resisted the Plan’s ambitions largely depending upon their political persuasion at the time. Labour-run Croydon Council, on the southern edge of the Greater London area, was one of the first out of the blocks, quickly establishing a set of planning principles to be followed by applicants wishing to bring forward small-scale development in suburban areas—generally towards the southern border with Surrey. It’s award-winning Suburban Design Guide was adopted in April 2019, and provided clear parameters for the transformation of large, land-hungry houses into efficient, mid-rise developments. Essentially, as long as developers followed the rules established by the guidance, there would be no reason for their applications to be rejected. Some examples provided within the document demonstrated how, for example, a pair of adjoining large houses could be turned into as many as 20 to 30 new homes.

Five years on from the adoption of the guidance, which was scrapped in 2022 by the incoming Conservative mayor, there is sufficient data to demonstrate the effect this policy had on housing delivery—and the figures are remarkable. In the four-year period between 2018 and 2021, Croydon managed to complete nearly 2,000 new homes on small sites within developments consisting of fewer than ten dwellings (noting that even this is below the London Plan’s small site threshold, which determines plot size but not the number of homes within it). The next highest delivering borough was Barnet, which in the same period delivered around a quarter of this figure.

The Suburban Design Guide neatly illustrated how larger areas of suburban housing could be intensified incrementally, resulting in a broader mix of smaller flats, townhouses and large family homes. This approach is borne out by the number of homes delivered in Croydon during a relatively short period of time: around 500 per year. There are 20 outer-London boroughs including Croydon. If the remaining 19 had managed to deliver housing on small sites at the same rate, we could have had another 25,000 homes built by now.

The Croydon experience provides a useful model for how suburban intensification might be achieved across the rest of the city. There are numerous benefits to this approach, in addition to the sheer number of new homes that could be delivered this way: smaller developments tend to rely more heavily on local supply chains, so can help reinvigorate local economies, providing jobs, skills and training. And, by reducing the barriers to entry through the mitigation of planning risk, developers are able to invest in better quality, more sustainable homes that meet local need—and significantly faster than large-scale housebuilding. The inclusion of policies which limit the net loss of family homes can also ensure that diversity of housing stock is maintained.

Our research has shown that implementing a similar policy across the whole of London’s suburbs within 800m of a station could enable the delivery of between 850,000 and a million homes through a modest uplift in density of just 25%, assuming no lower than 40 dwellings per hectare (dph), and no higher than 100dph. Even at this modest level, which would involve limited disruption to existing communities, the potential gains are huge.

The recent investigation by the Competition Markets Authority into housebuilding identified planning uncertainty as a significant barrier to the delivery of a new homes, and in particular, to the entry of small-scale developers into the market, stating that there is “evidence that problems in the planning systems may be having a disproportionate impact on SME housebuilders.”

Providing certainty through the planning system has to be a key tenet of any drive to improve housebuilding. A strong presumption in favour of development close to existing stations in urban areas would help in this regard, backed by clear and unambiguous guidance on what types of development would be acceptable, including clarity on building heights, privacy distances, overshadowing and access to natural daylight, and so on.

The 2017 draft London Plan stated that within close proximity to stations and town centres, “there is a need for the character of some neighbourhoods to evolve to accommodate additional housing. Therefore, the emphasis of decision-making should change from preserving what is there at the moment towards encouraging and facilitating the delivery of well-designed additional housing to meet London’s needs.” This text was expunged from the adopted version. Words to this effect should now be included within the National Planning Policy Framework, making an exception for areas protected by other heritage designations, such as conservation areas and proximity to listed buildings and so on. This direction should be accompanied by an instruction that local planning authorities develop clear design guidance to assist in the delivery of new homes on small sites. If they do not, then a default set of guidance should be established for applicants to fall back on until such time as this in put in place.

Suburban intensification is tricky, and alone will never be able to deliver all of the homes that the country needs. But experience from Croydon has demonstrated that when the right conditions are in place, it can be implemented quickly, and at scale. As the country recovers from a long period of stagnation, this is one way that we can not only build the homes we need—quickly, where they’re most needed—but also promote economic growth.